For getting the maximum of your training you have to apply these six important and basic principles of training – specificity, overload, progression, individualization, Adaptation, and Reversibility.

Training Principle 1: Specificity

The first principle is specificity, often referred to as the SAID ( specific adaptation to imposed demands ) principle, which states that the body will specifically adapt to the type of demand placed on it. The SAID principle says every sport poses its own unique demands and that in order to improve skills unique to a particular sport, it’s best to practice the moves used in that sport.

For example, If you want to be a great basketball player, running laps on the track will help your general conditioning but won’t improve your skills at throwing or the power and muscular endurance required to throw a ball in a game.

Another example is, that if the goals of the training program were to maximize strength gains, then performing low-intensity, high-volume exercise would not be specific to the objectives of that particular program. Likewise, one would not prepare for a marathon by concentrating solely on running short sprints.

Training should be SPECIFIC in:

Energy systems as used during competition

Speed of movement

Intensity/Volume

Muscle groups trained and involved

Range of motion

Training Principle 2: Overload

The overload principle is for training adaptations to occur, the muscle or physiological component being trained must be exercised at a level that it is not normally accustomed to.

So in order to see an increase in strength and endurance, you need to add new resistance or time/intensity to your efforts.

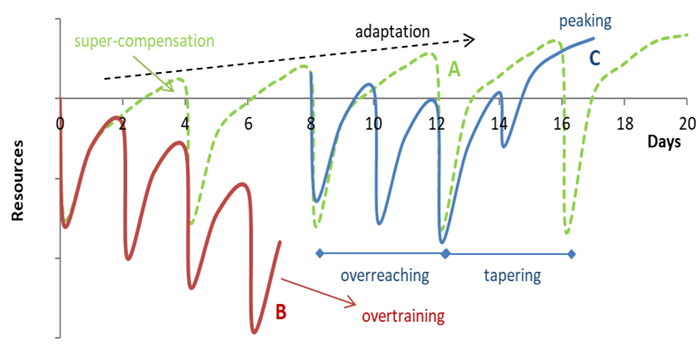

Training loads must be increased gradually to allow the body to adapt. Varying the frequency, type, volume, and intensity of the training load allows the body an opportunity to recover, and to over-compensate. Loading must continue to increase incrementally as adaptation occurs, otherwise, the training effect will plateau and further improvement will not occur.

Training Principle 3: Progression

The principle of overload states that a greater than normal stress or load on the body is required for training adaptation to take place. The body will adapt to this stimulus. Once the body has adapted then a higher stimulus is required to continue the change. In order for a muscle to increase strength, it must be gradually stressed by working against a load greater than it is used to.

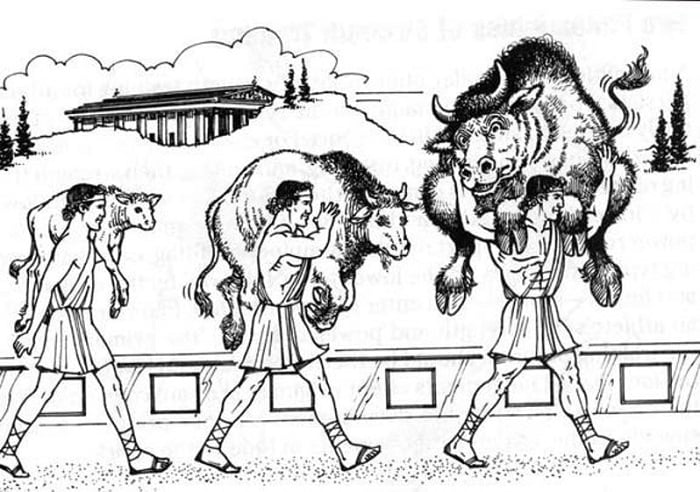

A simple and clear example to understand the progression principle is the story of the Greek myth about Milo of Croton. To become the world’s strongest man, Milo lifted and carried a calf every day, beginning in his teenage years. As the calf grew heavier, Milo grew stronger. By the time the calf was a full-grown bull, Milo was the world’s strongest man, thanks to long-term progression. This process of applying progressive overload should also occur continually throughout the resistance training program.

In general, weekly progressions should stay at +2–5% of the previous training week’s prescription, and the rate of progression will slow over time (i.e., a beginner will progress at a faster rate than an experienced trainee).

Training Principle 4: Individualization

This is a crucial principle, Contemporary training requires individualization. Despite what we are told, Everyone is different and responds differently to training. Some of these differences can be influenced by many characteristics; biological age, training age, gender, body size and shape, past injuries, and many more.

Individualization states that we are all physiologically, neurologically, and emotionally different, and therefore, each athlete must be treated according to his or her ability, potential, training age, Sex-based differences, and athlete’s rate of recovery.

Differences can be influenced by many characteristics; including

- Genetics and physical status (age, training age, gender, initial fitness level, muscle fibers, vo2max).

- Specific needs (prioritization based on strengths & weaknesses, or demands of sport or activity).

- Health or injury concerns may limit the exercises performed or the exercise intensity.

- Desired effort and motivation (is the program recreational, or is “maximal performance” desired?).

- Time availability (per workout and week).

- Availability and preference of equipment (e.g., free weights, machines, elastic bands).

- Environment factors (heat, cold, and humidity).

- Diet & sleep

Training Principle 5: Adaptation

Adaptation is how the body ‘programs’ muscles to remember particular activities, movements, or skills. By repeating that skill or exercise, the body adapts to the stress and the skill becomes easier to perform. The Principle of Adaptation explains why beginning exercisers are often sore after starting a new routine, but after doing the same exercise for weeks and months the athlete has little, if any, muscle soreness. This also explains the need to vary the routine and apply the Overload Principle if the continued improvement is desired.

Training Principle 6: Reversibility

This one is simple, USE IT OR LOSE IT. The principle of reversibility suggests that any improvement in physical fitness due to physical activity is entirely reversible When the training stimulus is removed or reduced. This principle suggests that regularity and consistency of physical activity are important determinants of both fitness maintenance and continued improvement. Reversibility is when training stops and the effects of the exercise done are lost, it takes less time to lose fitness than to gain it.

When the training stimulus is removed or reduced for an extended duration, the athlete is said to be detrained. The removal or reduction of the training stimulus may lead to performance decrements.

The extent of performance decrements relates to the length of the detraining or reduced training period and the type of activity.

Strength and power performances also decline during periods of detraining. The magnitude of the decline may depend on the training background, length of the training period before detraining, and the specific muscle group.

- Zatsiorsky VM, Kraemer WJ. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2004.

- Verkhoshanky Y, Verkhoshanky N. Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches. Rome, Italy: Verkhoshansky SSTM; 2011:274.

- Kraemer WJ, Deschenes MR, Fleck SJ. Physiological adaptations to resistance exercise. Implications for athletic conditioning. Sports Med. 1988;6(4):246–56.

- Stephen P. Bird, Kyle M. Tarpenning and Frank E. Marino. Designing Resistance Training Programmes to Enhance Muscular Fitness.Sports Med 2005; 35 (10): 841-851

- Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:674-688.

- Designing resistance training programs / Steven J. Fleck, William J. Kraemer. — Fourth edition.

- NASM PERSONAL FITNESS TRAINING.National Academy of Sports Medicine, Jones & Bartlett Learning